Three Playscripts. Silence; No-Man’s Land; Betrayal. 3 vols. 4to.

Book Description

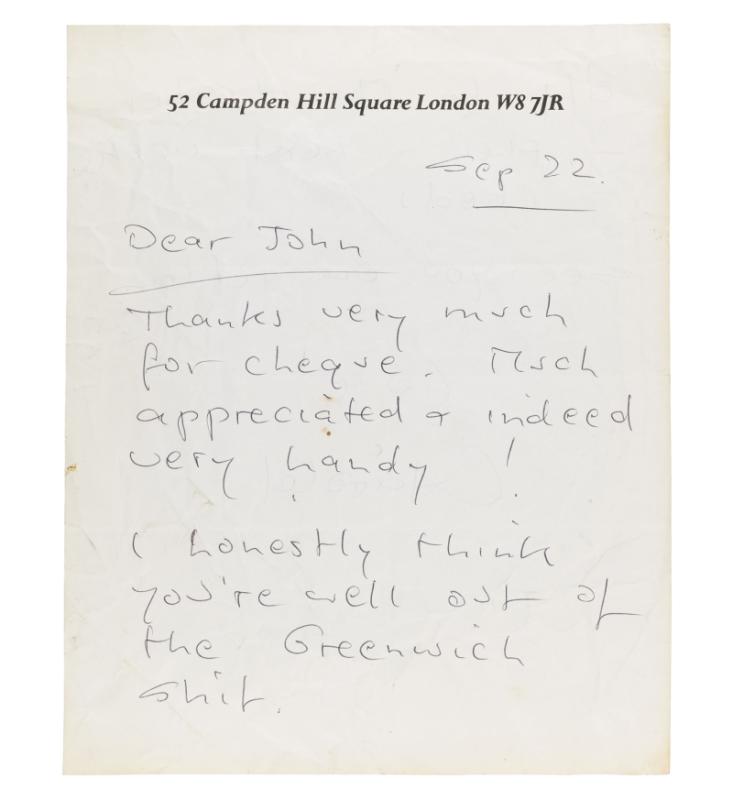

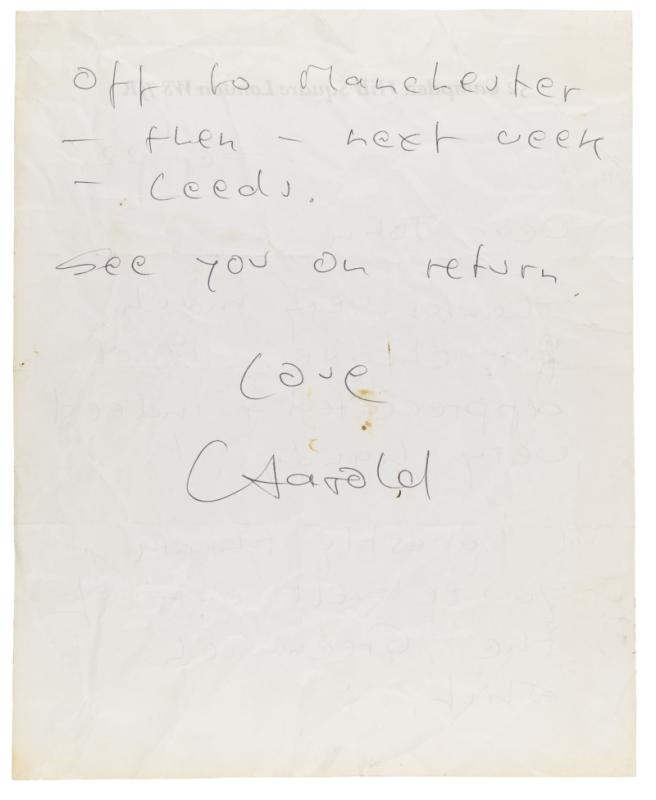

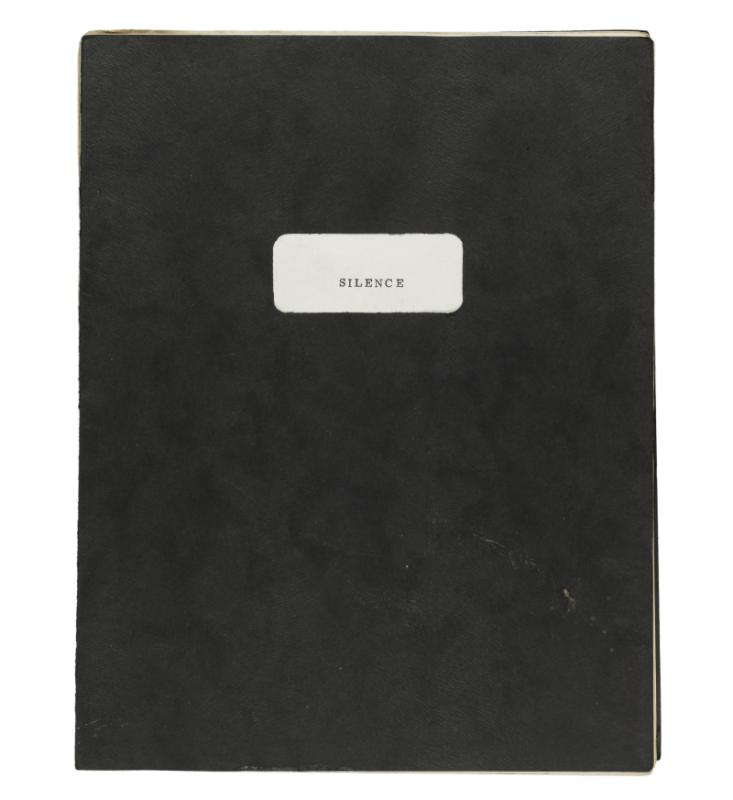

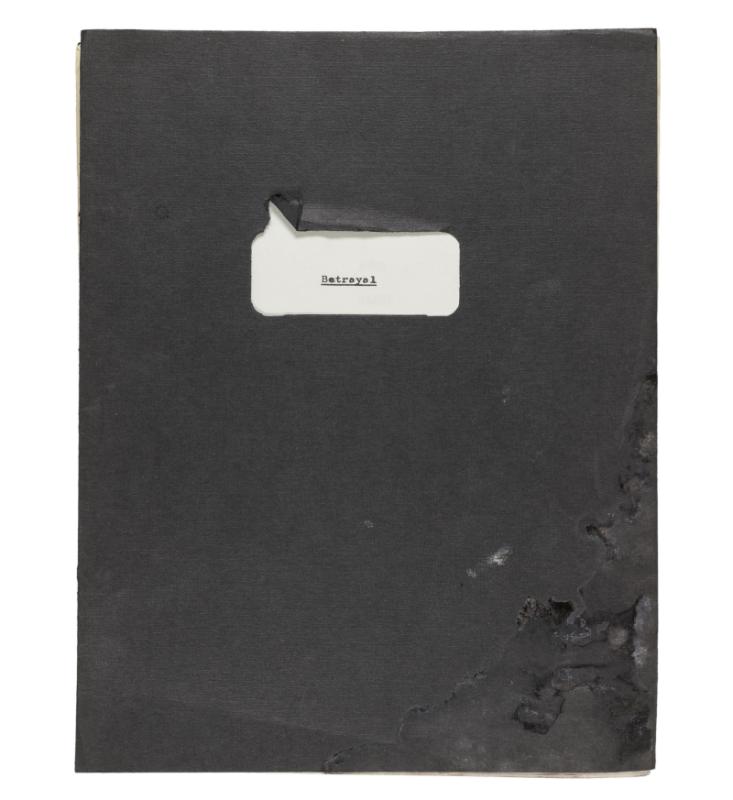

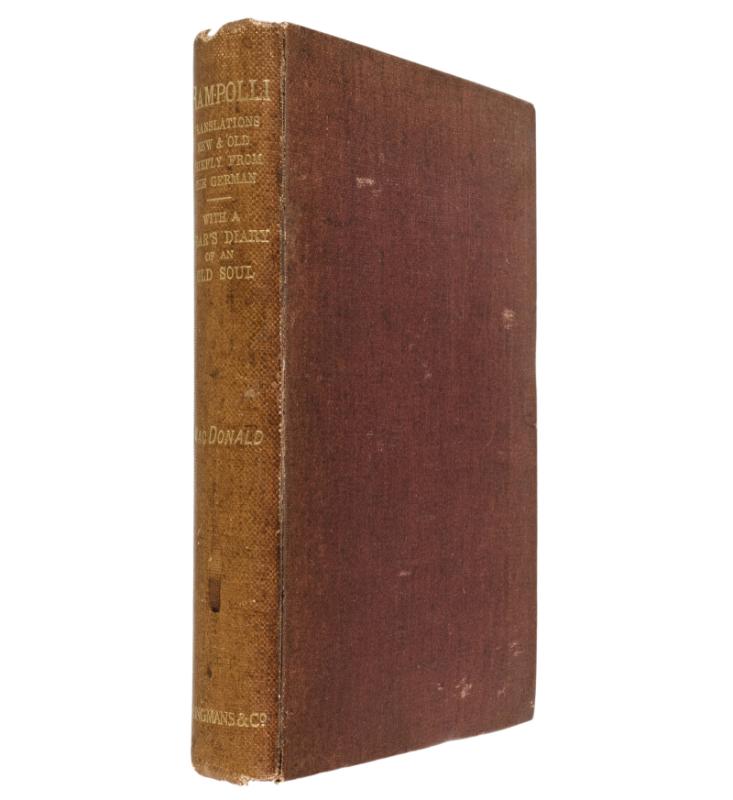

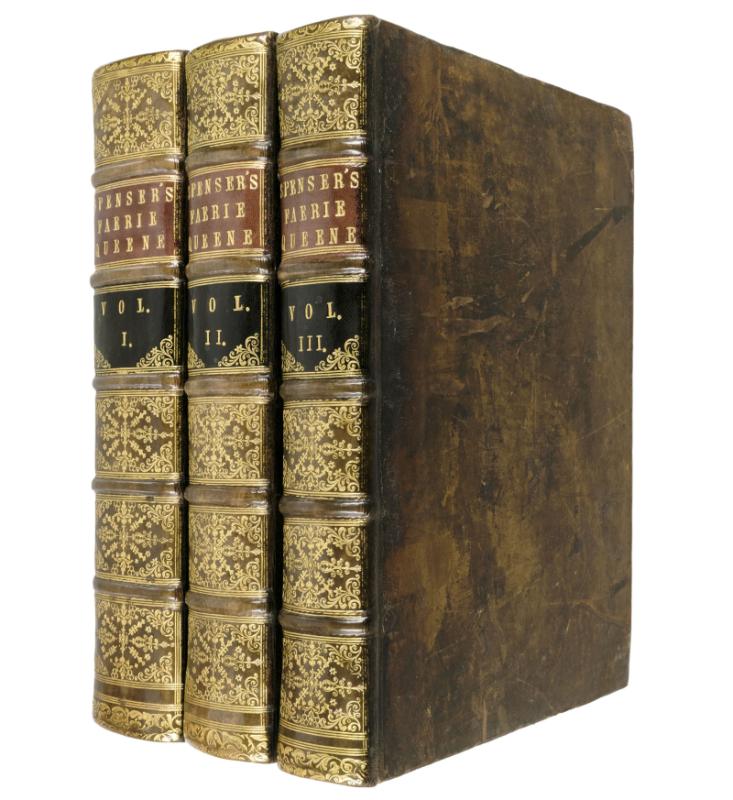

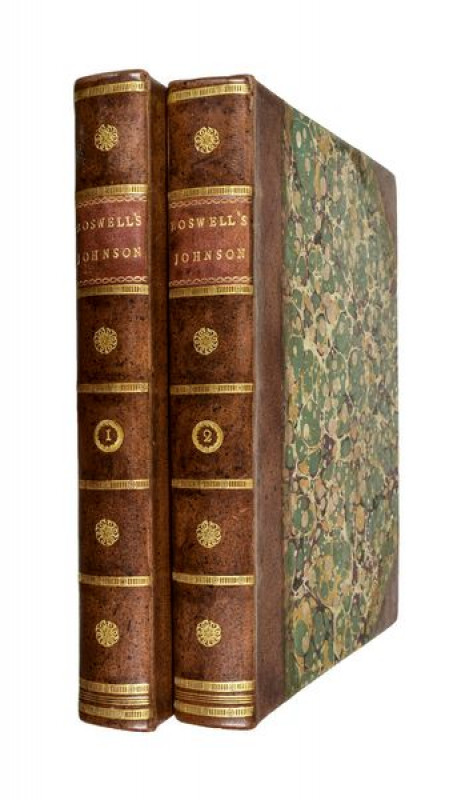

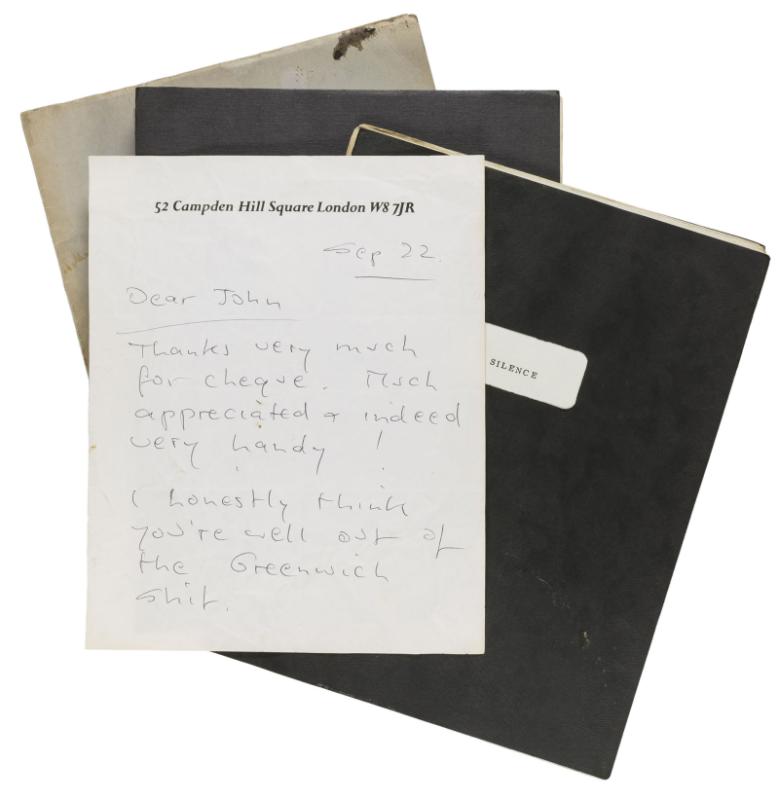

Three playscripts typed on versos only. SILENCE. Limp black card wrappers. Inscribed ‘Feb 1969 To John from Harold’ on titlepage. NO-MAN’S LAND. Limp drab card wrappers; marked, edges faded. Inscribed ‘To John from Harold’ on titlepage. BETRAYAL. Opening pages & edges marked, not affecting text. Limp black card wrappers; sl. torn, lower corner marked. Inscribed ‘To John from Harold’ on titlepage. 16-line ALS on headed paper loosely inserted; a little creased.

Dealer Notes

An excellent association. Three playscripts inscribed by the Nobel Prize-winner to the Welsh actor John Rees, 1927-1994. Rees was an early associate of Pinter, and appeared in a number of Pinter’s projects, including the films The Quiller Memorandum and The Go-Between, and most notably several early productions of The Caretaker in the part of Aston (a role he also played in the television movie, alongside Ian McShane). Rees was a close friend of both Pinter and his first wife, the actor Vivien Merchant, with whom he appeared in the 1960 Hampstead Theatre revival of Pinter’s first play, The Room. Pinter was not a faithful husband and conducted a long affair with Joan Bakewell, on which he drew heavily (and to great effect) for one of his greatest plays, Betrayal, included here. In 1980 he left Merchant for Antonia Fraser who moved into the marital home. Merchant became extremely depressed, moved in with John Rees (the presentee), began to drink heavily, and died two years later.

The ALS is typically Pinteresque: brief thanks for a ‘very handy’ cheque and a cryptic reassurance that ‘you’re well out of the Greenwich shit’.

The three plays are from Pinter’s middle period and balance the quiet (somewhat mannered) menace of his early work with the overt brutality he explored from the 1980s onwards. Each play is representative of a different aspect of Pinter’s genius. Silence, one of his most complex and underrated plays, exemplifies the use of pauses, and explores Pinter’s extraordinary talent for the unsaid. As he wrote of his own work: the ‘speech we hear is an indication of that which we don't hear. It is a necessary avoidance’.

No-Man’s Land, in which two drunk writers (one successful, one marginal; each character, of course, contains some of Pinter) spar verbally in a decrepit London house, was described by biographer Michael Billington as a ‘haunting weird play’, opaque but effective. He goes on to call it ‘a masterly summation of all the themes that have long obsessed Pinter: the fallibility of memory, the co-existence in one man of brute strength and sensitivity, the ultimate unknowability of women, the notion that all human contact is a battle between who and whom. ... It is in no sense a dry, mannerist work but a living, theatrical experience full of rich comedy in which one speech constantly undercuts another.’

Betrayal is widely - and rightly - considered one of the playwright’s greatest works, in which an ordinary situation, an extramarital affair, is rendered utterly horrifying. A reverse chronological structure is employed to evoke terror and alienation with enormous emotional veracity. It is unwise to call Pinter’s work surreal, he was a great observer of dialogue and day-to-day life, and the discomfort of his work stems from a stark presentation - rather than an obfuscation - of reality.

The ALS is typically Pinteresque: brief thanks for a ‘very handy’ cheque and a cryptic reassurance that ‘you’re well out of the Greenwich shit’.

The three plays are from Pinter’s middle period and balance the quiet (somewhat mannered) menace of his early work with the overt brutality he explored from the 1980s onwards. Each play is representative of a different aspect of Pinter’s genius. Silence, one of his most complex and underrated plays, exemplifies the use of pauses, and explores Pinter’s extraordinary talent for the unsaid. As he wrote of his own work: the ‘speech we hear is an indication of that which we don't hear. It is a necessary avoidance’.

No-Man’s Land, in which two drunk writers (one successful, one marginal; each character, of course, contains some of Pinter) spar verbally in a decrepit London house, was described by biographer Michael Billington as a ‘haunting weird play’, opaque but effective. He goes on to call it ‘a masterly summation of all the themes that have long obsessed Pinter: the fallibility of memory, the co-existence in one man of brute strength and sensitivity, the ultimate unknowability of women, the notion that all human contact is a battle between who and whom. ... It is in no sense a dry, mannerist work but a living, theatrical experience full of rich comedy in which one speech constantly undercuts another.’

Betrayal is widely - and rightly - considered one of the playwright’s greatest works, in which an ordinary situation, an extramarital affair, is rendered utterly horrifying. A reverse chronological structure is employed to evoke terror and alienation with enormous emotional veracity. It is unwise to call Pinter’s work surreal, he was a great observer of dialogue and day-to-day life, and the discomfort of his work stems from a stark presentation - rather than an obfuscation - of reality.

Author

PINTER, Harold.

Date

1969-1978

Friends of the PBFA

For £10 get free entry to our fairs, updates from the PBFA and more.

Please email info@pbfa.org for more information