“The American Toilet” conduct book. First edition 1827. Rare complete.

Book Description

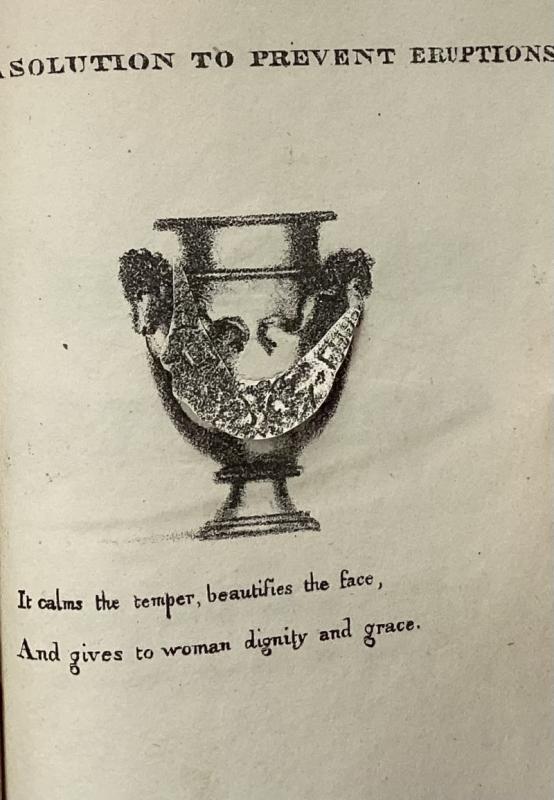

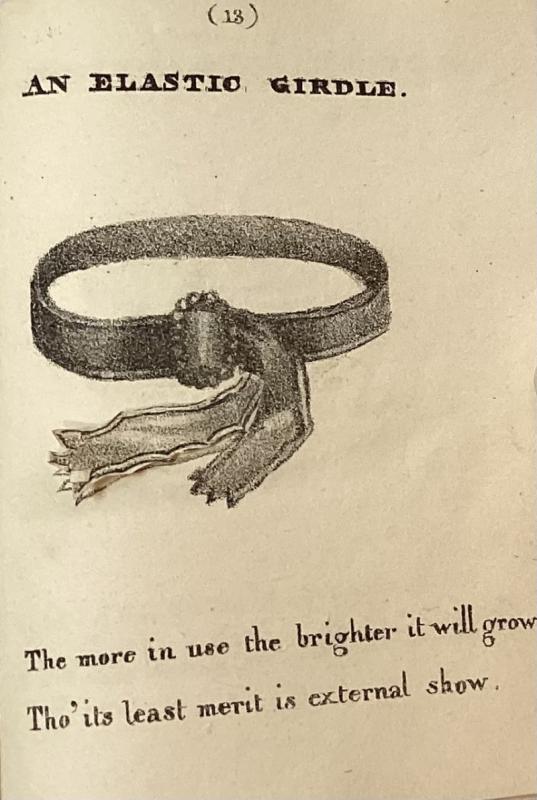

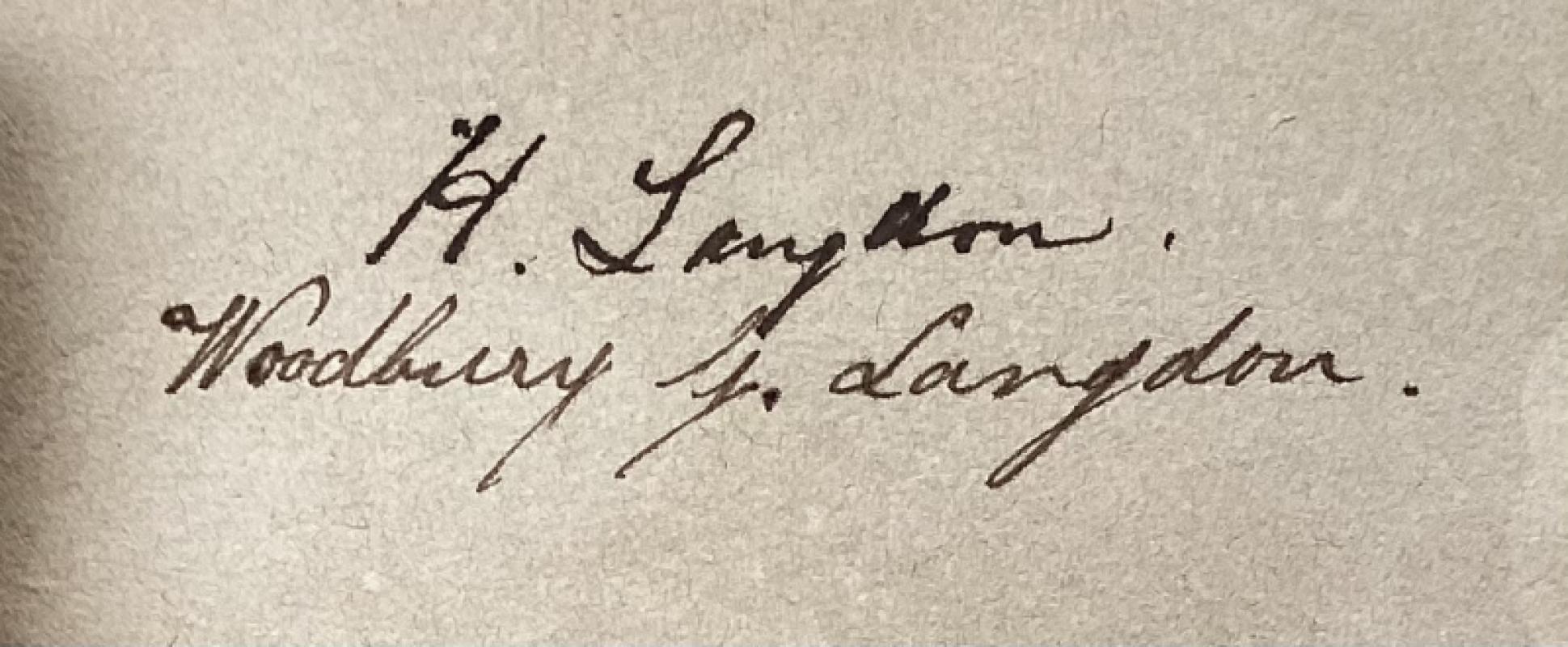

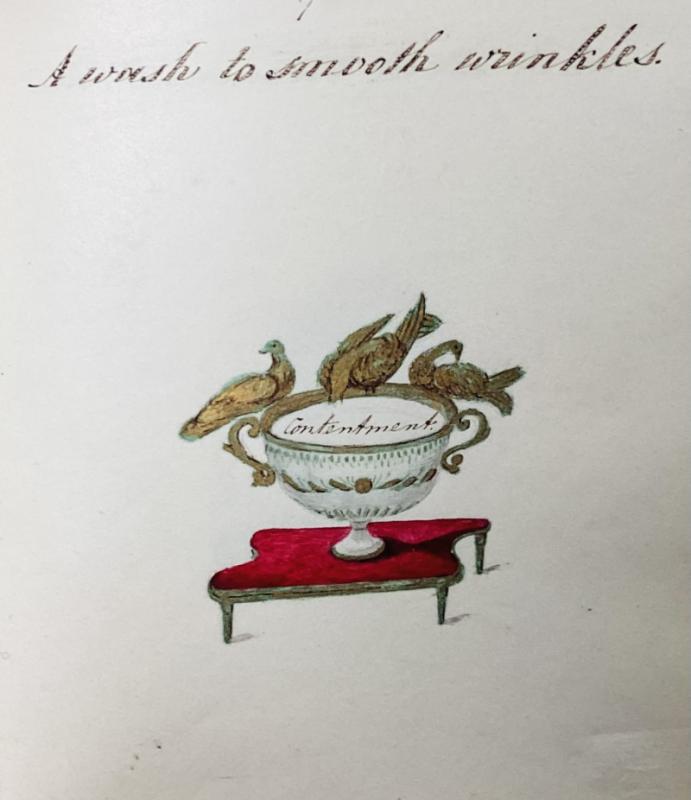

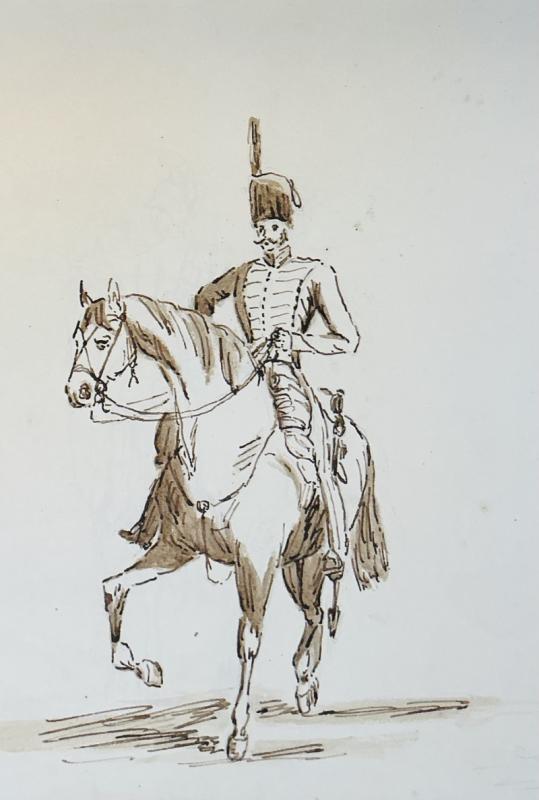

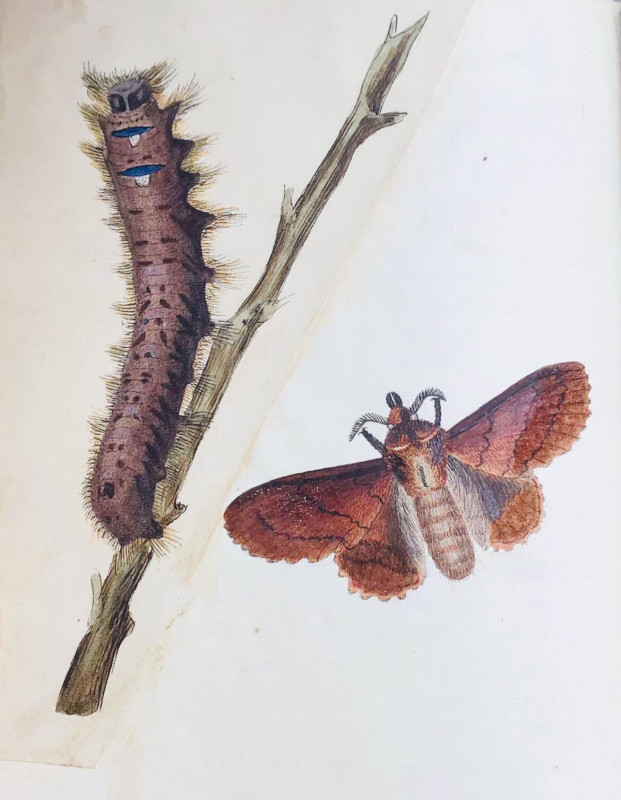

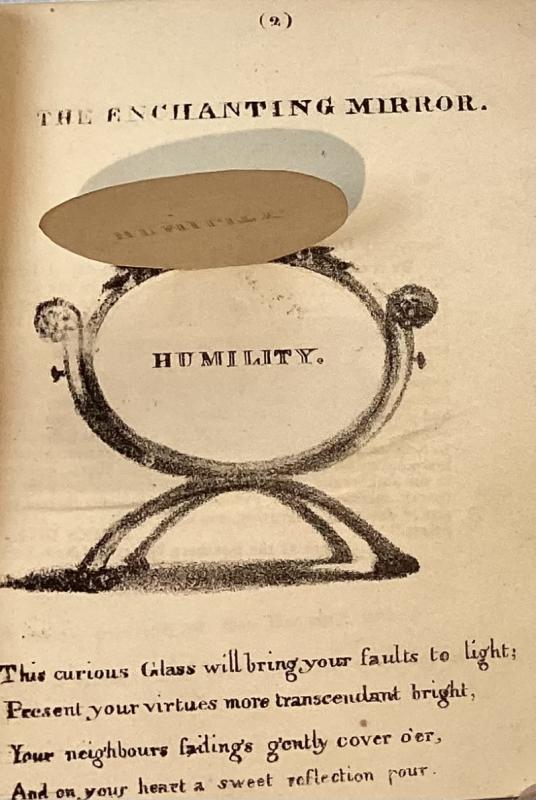

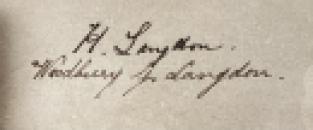

MURRAY, Hannah, née Lindlay. [Attrib.] The American Toilet. New York: Printed and published at Imbert’s Lithographic, 1827. A movable “riddle” conduct book from Imbert’s Lithographic Office, and one of the first U.S. books printed entirely by lithography. Pp 17. Each leaf shows a toiletry item with a hinged flap hiding a moral virtue beneath [e.g., The flap on the image “A Wash to Smooth Wrinkles”, reveals the word “Contentment”.] Approx. 3.75" × 4.75", bound in the original marbled wraps, sewn binding. Most unusually, all the flaps are complete. Most surviving copies are in poor condition and with missing flaps. There is a little loss to the spine, the rear wrapper starting but holding. Ownership inscriptions on the endpaper for H Langdon, above Woodbury Langdon, but sound and with all pages secure and relatively unmarked.

The Winterthur Library states that according to the 1867 edition of this work, sisters Hannah and Mary of New York designed "The Toilet" by cutting out pictures from papers and pasting them into blank books, writing the inscriptions themselves. They sold these booklets to raise money for charities. Eventually, the idea was adapted to a printed version, copies of which are in the Rare Books area of the Winterthur Library.Hannah was born in Pennsylvania. In 1766, she wed John Murray. To this union were born the following children: Elizabeth, Hannah, John, Mary, Susan, Robert, and George. She passed away in Manhattan, New York. Wikipedia:

“Woodbury Langdon [1739-1805] Continental Congressman, of Portsmouth, New Hampshire. Henry Sherburne Langdon [1766-1857],cashier of the Union Bank & Navy Agent of Portsmouth, New Hampshire.

Woodbury Langdon was an American merchant, politician and justice. He was the brother of John Langdon, a Founding Father who served as both senator from and Governor of New Hampshire, and father-in-law of Edmund Roberts. Langdon attended the Latin grammar school at Portsmouth, then went into the counting house of Henry Sherburne, a prominent local merchant. He was described as a large, handsome man—indeed, a contemporary recalled that the three handsomest men of that era were George Washington, Lord Whitworth and Woodbury Langdon. Langdon's business success enabled him to build and furnish a substantial home on State Street. In 1781, his home was destroyed in a fire which started in the barn where the Music Hall now stands. He rebuilt the three-story brick mansion in 1785, called "the costliest house anywhere about," and occupied it for the remainder of his life. When the American Revolutionary War broke out in 1775, Langdon sailed to London to secure considerable monies he had invested there. The attempt was unsuccessful, and two years later he left empty-handed for New York. Upon arrival, Commander-in-Chief General William Howe suspected Langdon's loyalty to the Crown, and consequently restricted him to the city. Entreaties to release Langdon, written both by his prominent friends in England and younger brother, John, were ignored. Nevertheless, in December 1777 he managed to escape. If Langdon's leanings towards American Independence were at all uncertain before his confinement in Manhattan, they became unmistakable afterwards. In spring of 1779, he was elected as one of New Hampshire's delegates to the Continental Congress, serving a year. In 1780, 1781 and 1785 he was re-elected, but chose to remain in New Hampshire and serve at the revolutionary capital in Exeter, where he was a representative from 1778 to 1779 and a member of the Executive Council from 1781 to 1784. Langdon was appointed an associate justice of the New Hampshire Superior Court in 1782. He resigned after a year despite the legislature's repeated requests that he remain in office. In 1786, he again accepted the job and held it until January 1791. But on June 17, 1790, he became the first state superior court justice to be impeached. The New Hampshire House of Representatives voted 35-29 to impeach him for neglecting his duties, finding that he had failed to attend sessions of the court in outlying counties in order to pursue his commercial interests in Portsmouth. It also resented his charge that the legislature failed to provide honorable salaries for judges and interfered in court decisions, calling his conduct " ... impertinent and unbecoming to his office." The trial in the state senate was postponed, with Langdon resigning his position before it could commence. In the meantime, President Washington had appointed him in December 1790 as a commissioner to settle Revolutionary War claims. Langdon attempted a comeback by running in two successive elections for Congress in New Hampshire's at-large district as the Democratic-Republican nominee in 1796 and an October 1797 special election, but he finished 6th in the former[2] and lost to Peleg Sprague in the latter.[3] A final campaign for this seat came in a November 1799 special election after Sprague declined to serve, but Langdon lost in a landslide to James Sheafe. Langdon died in Portsmouth on January 13, 1805, and was buried in the North Cemetery at Portsmouth.

In 1765, Langdon married Henry Sherburne's daughter Sarah, who was then 16. Their children included: Henry Sherburne Langdon [1766-1858], who married Ann Eustis, the sister of William Eustis. They had a son named John Agustine Langdon Eustis, who emigrated to Argentina and died in Buenos Aires in 1876. He had many descendants, who in turn married into the high society of Argentina, such as the Saenz Valiente, Pueyrredon, Obarrio and Beccar Varela families. Woodbury Langdon [1768-1770] Sarah Langdon [1770-1795], the wife of Robert Harris of Portsmouth, Mary Ann Langdon [b. 1772], Amelia Langdon [b. 1773], Woodbury Langdon [b. 1774], who became a resident of New Orleans, and died without marrying.”

Author

MURRAY, Hannah,

Friends of the PBFA

For £10 get free entry to our fairs, updates from the PBFA and more.

Please email info@pbfa.org for more information