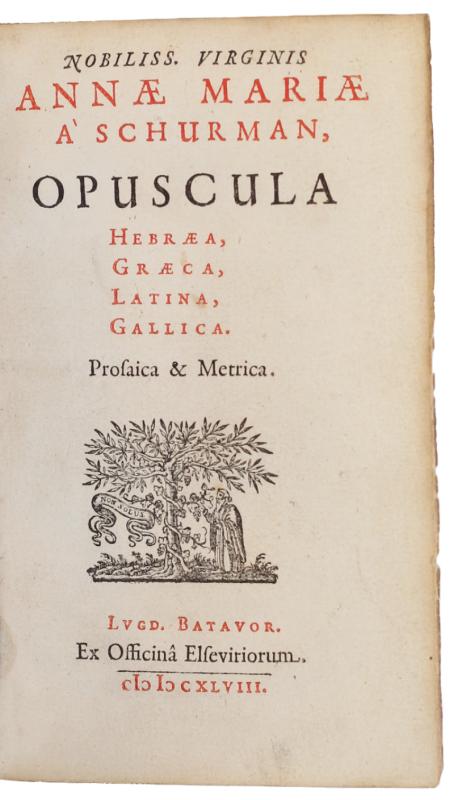

Opuscula hebraea, graeca, latina, gallica: prosaica & metrica. Edited by Friedrich Spanheim

Book Description

FIRST EDITION OF AN INFLUENTIAL COLLECTION OF WRITINGS BY THE CELEBRATED SCHOLAR AND LINGUIST ANNA MARIA VAN SCHURMAN, ‘THE DUTCH MINERVA’

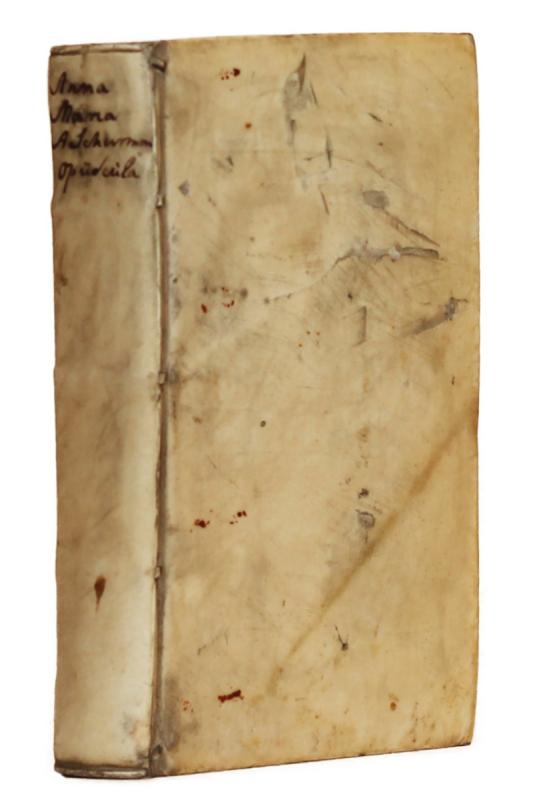

Octavo (154 x 95mm), pp. [2 (title, verso blank)], [4 (Friedrich Spanheim’s address to the reader)], 374, [2 (final blank l.)]. Printed in roman, Greek, Hebrew, and Arabic types. Title printed in red and black, and with wood-engraved Elzevier device [‘Solitaire’]. Wood-engraved head- and tailpieces, and initials. (A few light marks, faint, mainly marginal damp-marking, lacking l. *4 with portrait as often.) Contemporary vellum, spine lettered in ink [?]in a later hand. (Slightly marked, some cockling and cracking, causing small tears and losses on lower pastedown, some splitting on bookblock, front endpapers possibly replaced in 18th or 19th century.) A very good copy. ¶¶

Provenance: [?]18th- or 19th-century manuscript note in Latin on front free endpaper [?]by a bookseller – trace of historic paper label on upper pastedown – later pencilled notes by Dutch and British booksellers on front free endpaper – Stephen John Keynes OBE, FLS (1927-2017). ¶¶¶

Octavo (154 x 95mm), pp. [2 (title, verso blank)], [4 (Friedrich Spanheim’s address to the reader)], 374, [2 (final blank l.)]. Printed in roman, Greek, Hebrew, and Arabic types. Title printed in red and black, and with wood-engraved Elzevier device [‘Solitaire’]. Wood-engraved head- and tailpieces, and initials. (A few light marks, faint, mainly marginal damp-marking, lacking l. *4 with portrait as often.) Contemporary vellum, spine lettered in ink [?]in a later hand. (Slightly marked, some cockling and cracking, causing small tears and losses on lower pastedown, some splitting on bookblock, front endpapers possibly replaced in 18th or 19th century.) A very good copy. ¶¶

Provenance: [?]18th- or 19th-century manuscript note in Latin on front free endpaper [?]by a bookseller – trace of historic paper label on upper pastedown – later pencilled notes by Dutch and British booksellers on front free endpaper – Stephen John Keynes OBE, FLS (1927-2017). ¶¶¶

Dealer Notes

First edition. The celebrated scholar Anna Maria van Schurman (1607-1678) was born in Cologne to a very devout Reformed family which confessed an orthodox Calvinism. Her ‘exceptional artistic talents and intellectual abilities manifested themselves very early’, and – remarkably – she ‘was given the same education as her brothers, and under the tutelage of her father she learned quickly and eagerly a wide variety of subjects: arithmetic, geography, astronomy, music, Latin, Greek, Hebrew, and a large number of Oriental and modern languages, as well as theology, which became increasingly important for her’ (M. Bijvoet, ‘Anna-Maria van Schurman 1607-1678’ in K.M. Wilson, P. Schlueter, J. Schlueter (eds), Women Writers of Great Britain and Europe: An Encyclopedia (New York and London, 1997), pp. 419-420 at pp. 419-420). ¶¶

Like many other Reformed Germans, to avoid persecution the van Schurman family emigrated to the Netherlands in 1615, where they settled in Utrecht. In 1623 the family moved to Franeker, so that Anna Maria van Schurman’s brothers could study at the renowned university in the city, but, following the death of their father shortly afterwards, the family returned to Utrecht. In 1636 the new university at Utrecht was opened, and an ode to celebrate the event was commissioned from van Schurman (‘Inclytae et antiquae urbi Trajectinae Nova Academia nuperrime donatae gratulatur Anna Maria a Schurman’), in which she bemoaned the exclusion of women from the institution’s hallowed halls. Nonetheless, Gisbert Voetius, the Rector of Utrecht University and an influential figure in the Dutch Reformed Church, allowed van Schurman to attend lectures at the university (although she listened from a place which was concealed from the other students) and she also took part in the university’s disputations – thus making her the first female university student in Holland (and, quite probably, Europe). ¶¶

Van Schurman ‘elicited admiration for her erudition, particularly her proficiency in many languages – Dutch, Latin, Greek, Hebrew, German, English, French and Italian, also Syriac, Chaldaeic, Arabic and Turkish, not to mention Ethiopian, for which she wrote a grammar. She used letters, a genre more easily accessible to women than sermons or treatises, as a medium to intervene in the scholarly debates of her time. She corresponded with women and men all over Europe, with philosophers, such as Descartes against whom she eventually turned, following the narrow- minded example of the church, with theologians, physicians, poets and writers, with the Queen of Sweden and the princess Elizabeth, whose mother had been the “winter queen” of Bohemia’ (W. St Clair and I. Maassen (eds), Conduct Literature for Women, Part II, 1640-1710 (Abingdon and New York, 2016), pp. 215-216). The death of van Schurman’s mother in 1637, meant she became responsible for the household, and, some years later, the care of two elderly aunts Agnes and Sybille von Harff (with whom she would stay in Cologne in 1653-1654, thus allowing some limited participation in the intellectual life of the city). ¶¶

Anna Maria van Schurman’s writings had first appeared in print in 1636, but the publication of Opuscula hebraea, graeca, latina, gallica: prosaica & metrica was instrumental in establishing her international reputation. The volume was edited by Friedrich Spanheim, Rector of Leiden University, where he was professor of theology, and it collected both published and unpublished writings by van Schurman, in a variety of languages. Although the author had initially doubted the worth of or need for the volume, she was delighted by Spanheim’s edition, as she wrote to him on 15 August 1648 after receiving a copy: ‘[l]es exemplaires de mes letters, qu’il vous a plû m’envoyer, tesmoignent assez, combié je suis redevable à vostre affection & courtoisie, qui leur ont procure un si beau jour’ (Opuscula hebraea, graeca, latina, gallica: prosaica & metrica (Leiden, 1650), p. 375). The first edition was very well received, and Spanheim was working on a second edition at the time of his death in 1649. This second, revised edition (which included the letter quoted above) was published by the Elzeviers in 1650, and a third edition was published at Utrecht by Johannes Janssonius van Waesberge I in 1652. All three of these editions included an engraved portrait of the author, but it is often missing (as here); indeed, Willems, writing in 1880, commented that the engraved portrait ‘manque souvent, dans les trois éditions’. ¶¶

Despite the fame of the author – who was known to her contemporaries as the ‘Star of Utrecht’ or the ‘Dutch Minerva’ – and its positive reception, no further editions of Opuscula hebraea, graeca, latina, gallica: prosaica & metrica were published in Holland during the seventeenth century. This may be due primarily to two reasons, one personal and one beyond the author’s control; in the years following the publication of the book, its author had moved away from the Reformed Church and had been increasingly drawn to the teachings of Jean de Labadie, a former Jesuit who had become a Reformed minister and advocated a radical reformation of the Reformed Church’s practices. Anna Maria van Schurman’s brother Johan Godschalk van Schurman (c. 1605-1664) had met de Labadie in Geneva in 1662, and both siblings corresponded with de Labadie. Following a letter from Anna Maria van Schurman inviting him to Utrecht, de Labadie arrived in the city in 1666, and during the following year van Schurman became fully committed to the doctrines of Labadie, renouncing her previous life to join his community and leaving Utrecht for good in 1669. While she continued to publish on theological questions as a Labadist, van Schurman may have prohibited further editions of her earlier works; additionally, the widespread unpopularity of the Labadists may have deterred potential publishers. The second reason was the inclusion of the book on the Index librorum prohibitorum of the Roman Catholic Church in 1658 (cf. P. van Beek, The First Female University Student: Anna Maria van Schurman (1636) (Utrecht, 2010), p. 107). ¶¶

This copy is bound in a contemporary vellum binding and has an early manuscript note on the front free endpaper describing it as a ‘Liber rar[issim]us’ and citing Johann Vogt’s Catalogus historico-criticus librorum rariorum, which first listed this title in the third edition of 1747. It was later in the library of the noted bibliophile Stephen Keynes, a great-grandson of Charles Darwin, the founder and chairman of the Charles Darwin Trust, and, like his father Sir Geoffrey Keynes, a member of the Roxburghe Club. ¶¶

J.-C. Brunet, Manuel du libraire et de l'amateur de livres (1864), vol. V, col. 230; STCN 83370219X; J. Vogt, Catalogus historico-criticus librorum rariorum (1793), pp. 772-773; A. Willems, Les Elzevier (1880), 649.

Like many other Reformed Germans, to avoid persecution the van Schurman family emigrated to the Netherlands in 1615, where they settled in Utrecht. In 1623 the family moved to Franeker, so that Anna Maria van Schurman’s brothers could study at the renowned university in the city, but, following the death of their father shortly afterwards, the family returned to Utrecht. In 1636 the new university at Utrecht was opened, and an ode to celebrate the event was commissioned from van Schurman (‘Inclytae et antiquae urbi Trajectinae Nova Academia nuperrime donatae gratulatur Anna Maria a Schurman’), in which she bemoaned the exclusion of women from the institution’s hallowed halls. Nonetheless, Gisbert Voetius, the Rector of Utrecht University and an influential figure in the Dutch Reformed Church, allowed van Schurman to attend lectures at the university (although she listened from a place which was concealed from the other students) and she also took part in the university’s disputations – thus making her the first female university student in Holland (and, quite probably, Europe). ¶¶

Van Schurman ‘elicited admiration for her erudition, particularly her proficiency in many languages – Dutch, Latin, Greek, Hebrew, German, English, French and Italian, also Syriac, Chaldaeic, Arabic and Turkish, not to mention Ethiopian, for which she wrote a grammar. She used letters, a genre more easily accessible to women than sermons or treatises, as a medium to intervene in the scholarly debates of her time. She corresponded with women and men all over Europe, with philosophers, such as Descartes against whom she eventually turned, following the narrow- minded example of the church, with theologians, physicians, poets and writers, with the Queen of Sweden and the princess Elizabeth, whose mother had been the “winter queen” of Bohemia’ (W. St Clair and I. Maassen (eds), Conduct Literature for Women, Part II, 1640-1710 (Abingdon and New York, 2016), pp. 215-216). The death of van Schurman’s mother in 1637, meant she became responsible for the household, and, some years later, the care of two elderly aunts Agnes and Sybille von Harff (with whom she would stay in Cologne in 1653-1654, thus allowing some limited participation in the intellectual life of the city). ¶¶

Anna Maria van Schurman’s writings had first appeared in print in 1636, but the publication of Opuscula hebraea, graeca, latina, gallica: prosaica & metrica was instrumental in establishing her international reputation. The volume was edited by Friedrich Spanheim, Rector of Leiden University, where he was professor of theology, and it collected both published and unpublished writings by van Schurman, in a variety of languages. Although the author had initially doubted the worth of or need for the volume, she was delighted by Spanheim’s edition, as she wrote to him on 15 August 1648 after receiving a copy: ‘[l]es exemplaires de mes letters, qu’il vous a plû m’envoyer, tesmoignent assez, combié je suis redevable à vostre affection & courtoisie, qui leur ont procure un si beau jour’ (Opuscula hebraea, graeca, latina, gallica: prosaica & metrica (Leiden, 1650), p. 375). The first edition was very well received, and Spanheim was working on a second edition at the time of his death in 1649. This second, revised edition (which included the letter quoted above) was published by the Elzeviers in 1650, and a third edition was published at Utrecht by Johannes Janssonius van Waesberge I in 1652. All three of these editions included an engraved portrait of the author, but it is often missing (as here); indeed, Willems, writing in 1880, commented that the engraved portrait ‘manque souvent, dans les trois éditions’. ¶¶

Despite the fame of the author – who was known to her contemporaries as the ‘Star of Utrecht’ or the ‘Dutch Minerva’ – and its positive reception, no further editions of Opuscula hebraea, graeca, latina, gallica: prosaica & metrica were published in Holland during the seventeenth century. This may be due primarily to two reasons, one personal and one beyond the author’s control; in the years following the publication of the book, its author had moved away from the Reformed Church and had been increasingly drawn to the teachings of Jean de Labadie, a former Jesuit who had become a Reformed minister and advocated a radical reformation of the Reformed Church’s practices. Anna Maria van Schurman’s brother Johan Godschalk van Schurman (c. 1605-1664) had met de Labadie in Geneva in 1662, and both siblings corresponded with de Labadie. Following a letter from Anna Maria van Schurman inviting him to Utrecht, de Labadie arrived in the city in 1666, and during the following year van Schurman became fully committed to the doctrines of Labadie, renouncing her previous life to join his community and leaving Utrecht for good in 1669. While she continued to publish on theological questions as a Labadist, van Schurman may have prohibited further editions of her earlier works; additionally, the widespread unpopularity of the Labadists may have deterred potential publishers. The second reason was the inclusion of the book on the Index librorum prohibitorum of the Roman Catholic Church in 1658 (cf. P. van Beek, The First Female University Student: Anna Maria van Schurman (1636) (Utrecht, 2010), p. 107). ¶¶

This copy is bound in a contemporary vellum binding and has an early manuscript note on the front free endpaper describing it as a ‘Liber rar[issim]us’ and citing Johann Vogt’s Catalogus historico-criticus librorum rariorum, which first listed this title in the third edition of 1747. It was later in the library of the noted bibliophile Stephen Keynes, a great-grandson of Charles Darwin, the founder and chairman of the Charles Darwin Trust, and, like his father Sir Geoffrey Keynes, a member of the Roxburghe Club. ¶¶

J.-C. Brunet, Manuel du libraire et de l'amateur de livres (1864), vol. V, col. 230; STCN 83370219X; J. Vogt, Catalogus historico-criticus librorum rariorum (1793), pp. 772-773; A. Willems, Les Elzevier (1880), 649.

Author

SCHURMAN, Anna Maria van

Date

1648

Publisher

Leiden: ‘Officinâ Elseviriorum’ [i.e. Bonaventure and Abraham Elzevier]

Friends of the PBFA

For £10 get free entry to our fairs, updates from the PBFA and more.

Please email info@pbfa.org for more information