Liverpool Porcelain 1765 - 1804

Book Description

.

Dealer Notes

Review by Brian Gallagher

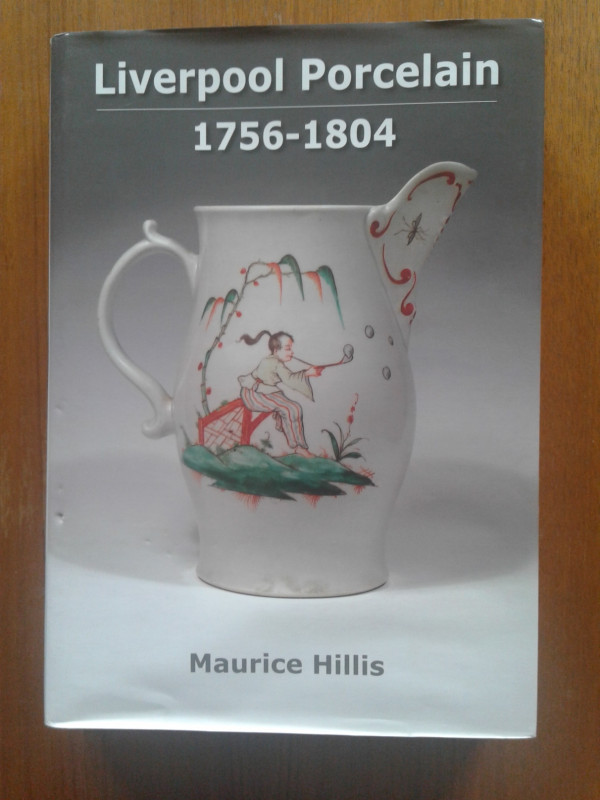

Liverpool Porcelain, 1756–1804

Maurice Hillis. Liverpool Porcelain, 1756–1804. Great Britain: Maurice Hillis, 2011. 564 pp.; 1,300 color illus., bibliography, index.

Liverpool Porcelain, 1756–1804 is the culmination of more than thirty years of research by Maurice Hillis, an independent ceramics historian and collector who has lectured and published widely on eighteenth- and nineteenth-century English ceramics.[1] In this book, Hillis set for himself a formidable goal: to offer clarity and guidance on a complex subject that has long confused collectors and ceramics scholars alike. Porcelain was made at seven sites in Liverpool in the second half of the eighteenth century, yet none of the factories used a distinct mark, nor are there extant pattern and shape books for any of them. In addition, there are close resemblances among products made at many of the Liverpool factories, so it has often proven very difficult to attribute specific objects correctly. Earlier specialists on Liverpool porcelain did attempt to assign specific wares to each factory, but in the absence of factual evidence mistakenly included objects produced in Worcester, London, or Staffordshire.[2] Hillis builds on the important efforts of his predecessors by incorporating recent scholarship along with 1,300 color illustrations to provide a comprehensive, well-documented study of each factory and its output. As Geoffrey Godden vividly proclaims in the foreword to Liverpool Porcelain, “never again will the city name be used as a very convenient ceramic dustbin for all those pieces that did not fit the old, fashionable groupings” (p. ix).

Hillis divides his book into fifteen chapters, the first two of which offer a brief overview of eighteenth-century Liverpool, its ceramics industry in general, and its porcelain sites in particular. Nine chapters are devoted to individual factories. Each of these chapters follows a similar format, beginning with a biography of the factory’s founder and a description of the factory’s location, including a detail from a street map contemporaneous with the factory’s operation. The author includes relevant discussion on business partners, workers, and apprentices. He details the factors utilized in making his attributions, including archeological evidence, dated objects, decoration, and type of porcelain body.[3] Hillis concludes these chapters with a thorough analysis of the wares made at each factory, presented according to form.[4] He carefully notes those elements—handles, spouts, molded patterns, and so on—that distinguish one factory’s output from another. Each chapter is considerably enhanced by copious illustrations.

The most impressive aspect of the publication is the thoroughness of the author’s research. He left no apparent stone unturned in his use of archival documents and archeological findings. In fact, as a member of the Liverpool Porcelain Rescue Group, Hillis quite literally turned over a good number of those stones himself, specifically at the Brownlow Hill site of William Reid’s factory and the Shaw’s Brow site of Samuel Gilbody’s factory.

Among the many archival sources he reviewed were corporation lease registers, rate books, fire insurance records, newspaper advertisements, polling lists, and freemen’s books. Hillis verified the location of William Reid’s factory on Brownlow Hill, for instance, by scrutinizing the lease register and a 1765 survey map, both preserved in the Liverpool Record Office (pp. 13–15). A Sun Fire Insurance policy dated October 22, 1746, provides the first mention of Richard Chaffers and Philip Christian as potters, plus documents their partnership in a pothouse on Shaw’s Brow (p. 139). On the other hand, the fact that Hillis was unable to find any documentary evidence for William Ball’s Ranelagh Street Pothouse, to which objects formerly were attributed, led him to conclude that the factory did not exist (pp. 494–95).

Hillis’s equally fruitful examination of sherds and wasters was especially critical in helping him to identify wares from the William Reid and Samuel Gilbody factories.[5] Many photo captions in the chapters for those factories mention the existence of sherds matching a particular feature of the illustrated object. Regarding the output of Thomas Wolfe & Company, Hillis credits Alan Smith, whose 1968 recovery of sherds from the factory’s site in Islington not only enabled later writers to attribute wares to this short-lived concern but also demonstrated that the factory produced a hybrid hard-paste porcelain and specialized in transfer-printed tea wares (pp. 477–78).

Hillis has visited many British and North American collections in order to inspect thousands of examples of Liverpool porcelain, as well as comparative examples from other factories. Every reader can benefit from the author’s unparalleled knowledge based on this decades-long effort. What English ceramics enthusiast would not enjoy learning that one can tell the difference between a Worcester teapot and a teapot of similar form by Philip Christian’s Liverpool factory because the underside of the latter’s lid flange is glazed whereas the former’s usually is not (p. 244)? Or that the high Chelsea ewers made by John Pennington can be distinguished from those made by Philip Christian, and later by Seth Pennington, because John’s ewer usually has an oval foot rim rather than an eight-lobed one, as well as a handle that is thicker and set lower on the vessel (p. 357)? Such satisfying morsels of connoisseurship are available on virtually every page on which Hillis discusses the products of the Liverpool factories.

Moreover, when lack of archeological evidence requires Hillis to rely solely on extant objects, his extension of a few definitive traits of a given factory’s wares into a fuller repertoire of characteristics identifying that maker is like watching a seasoned detective. Such was the case when Hillis endeavored to attribute wares to the factory of John Pennington, and later to his widow, Jane, who continued the factory after her husband’s death. John and Jane Pennington’s factory produced bone-ash porcelain. Hillis recognized that a number of bone-ash porcelain jugs had identical mask spouts and that some of the jugs bore dates ranging from 1772 to 1774. This period coincided with Philip Christian’s years of production, but Hillis was able to eliminate Christian as the maker of these jugs because his factory made only soaprock porcelain. John Pennington’s brother, James, was making bone-ash porcelain until 1773, but Hillis was able to eliminate him from consideration because one of the documentary jugs was dated 1790, long after James stopped making porcelain yet coinciding with the period when Jane Pennington was running the factory. Once Hillis was confident that the mask-spouted jugs were made at John and Jane Pennington’s factory, he could then study them for other distinctive features, such as the type of handle employed, and look for those on other ceramic forms (pp. 319–24).

While Hillis’s primary objective is to identify the full range of wares made at each factory, he loses no opportunity to showcase exceptional works, for another important goal of his is to challenge the ingrained perception among many collectors that Liverpool porcelain is of inferior quality to that made by other English factories. Hillis acknowledges that Liverpool factories, like many others, catered to a variety of markets, including those at the lower end of the economic scale. Nevertheless, he demonstrates that many Liverpool examples would hold their own against the best of its competitors. There is, for example, the covered vase, more than thirty inches tall and painted with a continuous Chinese landscape in underglaze blue, that was made at the Richard Chaffers factory (p. 215). Or the large Samuel Gilbody jug delicately painted in polychrome enamels and featuring a Chinese junk sailing from its jetty on one side and a tall British ship on the other (p. 303). Hillis also includes a number of very rare forms, such as a cream basket and spoon made by William Reid (p. 70), a holy-water stoup by Philip Christian (p. 267), and a James Pennington sauceboat in the shape of a duck (p. 124).

Hillis’s comprehensive knowledge of Liverpool objects comes to bear significantly not only in the nine chapters focusing on individual factories but in three others as well. The first of these presents an illustrated list of all dated Liverpool porcelain known to the author, of which there are more than sixty examples. They are arranged in chronological order and briefly described, and for the reader’s convenience Hillis indicates which ones are in public collections. The other two chapters address underglaze-blue and overglaze-enamel transfer-printed decoration on Liverpool porcelain.

In the chapter on underglaze decoration, Hillis describes some 120 patterns, the most comprehensive list ever published. He names and illustrates each pattern and, most important, indicates which Liverpool factory or factories used the pattern. He also indicates when different versions of the same print enable one to make an attribution to a specific factory. For instance, two versions of the Chinese Lady with a Bird in a Cartouche pattern were developed, but one was used only by John Pennington, while the other was used only by his brother Seth (pp. 428–29). This chapter alone will make Hillis’s book an essential addition to the libraries of Liverpool porcelain collectors and other enthusiasts. The one regret is that the illustrations in this chapter are generally smaller than those in the individual factory chapters, so if the pattern under discussion happens to be fairly complex, its component parts may not be clear.

The author does not use the convenient list format for the enamel-printed patterns, but he reviews a wide variety of designs and always identifies the factory using the pattern. He focuses special attention on John Sadler, the renowned Liverpool printer who almost certainly bought Worcester and Longton Hall porcelain blanks to decorate and then resell but whose relationship with the Liverpool porcelain factories is more complicated. Sadler probably bought Liverpool blanks as well, but Hillis offers evidence indicating that Chaffers, Gilbody, and Reid commissioned Sadler to decorate their wares, which the respective factories would have then sold on their own. The Christian factory, meanwhile, might have been capable of doing its own enamel printing (p. 533; also p. 231). Hillis identifies Liverpool ceramic printers other than Sadler who possibly decorated porcelain produced in the city. He calls for more research to understand these Liverpool printer-factory relationships.

The last chapter addresses the marketing and distribution of Liverpool porcelain. Hillis specifies the newspapers, both local and as far away as in America, in which some of the Liverpool factories placed advertisements. He also lists place names inscribed on Liverpool porcelains or at which Liverpool sherds have been found, suggesting the geographic range of the factories’ markets. Ceramics in America readers will be interested to know that these archeological sites include Colonial Williamsburg; Portsmouth, New Hampshire; and Fort Michilimackinac, Michigan.

Minor inconveniences arise in using Liverpool Porcelain as a reference. For instance, the index could be more complete. Josiah Wedgwood, Robert Hancock, and other individuals important to the history of English ceramics (if not necessarily to Liverpool porcelain) make guest appearances in the chapters but are not listed in the index. In addition, with the exception of the public-collection photographs in the chapter on dated Liverpool wares, names of the objects’ owners appear only in a photograph-acknowledgments section. For readers wishing to see these pieces in person, credit lines in the captions would have been helpful, especially for objects owned by public institutions. Finally, it is not clear why the two chapters on printed decoration are not consecutive: underglaze patterns are the subject of chapter 9, enamel patterns are addressed in chapter 14.

These are trifling concerns that do not detract from the author’s herculean accomplishment, made all the more impressive by virtue of the fact that Hillis published the work himself. He has produced a meticulously researched, profusely illustrated text that will help scholars, collectors, dealers, and others to understand, at last, the historically complex subject of Liverpool porcelain. His publication manifests the scholarship and careful analysis that lie behind it, ensuring that it will be the definitive source on Liverpool porcelain for many decades to come.

Brian Gallagher

Curator of Decorative Arts, The Mint Museum

brian.gallagher@mintmuseum.org

[1]

Previous publications by Hillis on topics related to Liverpool porcelain include Maurice Hillis, “The Analysis of Shards from the Brownlow Hill Site in Liverpool,” English Ceramic Circle Transactions 18, pt. 2 (2003): 335–38; Maurice Hillis, “The Liverpool China Manufactory of Wm. Reid and Company: A Survey of Wares,” English Ceramic Circle Transactions 18, pt. 1 (2002): 58–90; Maurice Hillis, “The Porcelain of John and Jane Pennington, c. 1771–1794,” Northern Ceramic Society Journal 6 (1987): 1–22; Lyn Hillis and Maurice Hillis, “Late Christian or Early Pennington?,” Northern Ceramic Society Journal 5 (1984): 29–32. Hillis also served as chairman of the Northern Ceramic Society from 2001 to 2012.

[2]

The first author to write an account of Liverpool porcelain was Knowles Boney, Liverpool Porcelain of the Eighteenth Century and Its Makers (London: B. T. Batsford, 1957). He included wares now known to have been made in London, Staffordshire, and Worcester. Bernard Watney, in his two-part article “Four Groups of Porcelain: Possibly Liverpool,” English Ceramic Circle Transactions 4, pt. 5 (1959): 13–25, and English Ceramic Circle Transactions 5, pt. 1(1960): 42–52, made a groundbreaking effort to attribute works to specific factories, but he too included wares made in London and Staffordshire. He corrected this error in his Liverpool Porcelain of the Eighteenth Century (Somerset, Eng.: Richard Dennis, 1997).

[3]

With the exception of Thomas Wolfe’s Islington China Works, which produced a hybrid hard-paste porcelain, eighteenth-century Liverpool factories exclusively made either soft-paste porcelain with bone ash or soft-paste porcelain with soaprock.

[4]

Forms include coffee pots, cups and mugs, teapots, jugs, sauceboats, plates, and dishes.

[5]

The Liverpool Porcelain Rescue Group (LPRG) conducted digs at Reid’s factory site on Brownlow Hill in the late 1990s. Alan Smith excavated Gilbody’s factory site at Shaw’s Brow in 1966. LPRG conducted a second dig there in 1990.

Liverpool Porcelain, 1756–1804

Maurice Hillis. Liverpool Porcelain, 1756–1804. Great Britain: Maurice Hillis, 2011. 564 pp.; 1,300 color illus., bibliography, index.

Liverpool Porcelain, 1756–1804 is the culmination of more than thirty years of research by Maurice Hillis, an independent ceramics historian and collector who has lectured and published widely on eighteenth- and nineteenth-century English ceramics.[1] In this book, Hillis set for himself a formidable goal: to offer clarity and guidance on a complex subject that has long confused collectors and ceramics scholars alike. Porcelain was made at seven sites in Liverpool in the second half of the eighteenth century, yet none of the factories used a distinct mark, nor are there extant pattern and shape books for any of them. In addition, there are close resemblances among products made at many of the Liverpool factories, so it has often proven very difficult to attribute specific objects correctly. Earlier specialists on Liverpool porcelain did attempt to assign specific wares to each factory, but in the absence of factual evidence mistakenly included objects produced in Worcester, London, or Staffordshire.[2] Hillis builds on the important efforts of his predecessors by incorporating recent scholarship along with 1,300 color illustrations to provide a comprehensive, well-documented study of each factory and its output. As Geoffrey Godden vividly proclaims in the foreword to Liverpool Porcelain, “never again will the city name be used as a very convenient ceramic dustbin for all those pieces that did not fit the old, fashionable groupings” (p. ix).

Hillis divides his book into fifteen chapters, the first two of which offer a brief overview of eighteenth-century Liverpool, its ceramics industry in general, and its porcelain sites in particular. Nine chapters are devoted to individual factories. Each of these chapters follows a similar format, beginning with a biography of the factory’s founder and a description of the factory’s location, including a detail from a street map contemporaneous with the factory’s operation. The author includes relevant discussion on business partners, workers, and apprentices. He details the factors utilized in making his attributions, including archeological evidence, dated objects, decoration, and type of porcelain body.[3] Hillis concludes these chapters with a thorough analysis of the wares made at each factory, presented according to form.[4] He carefully notes those elements—handles, spouts, molded patterns, and so on—that distinguish one factory’s output from another. Each chapter is considerably enhanced by copious illustrations.

The most impressive aspect of the publication is the thoroughness of the author’s research. He left no apparent stone unturned in his use of archival documents and archeological findings. In fact, as a member of the Liverpool Porcelain Rescue Group, Hillis quite literally turned over a good number of those stones himself, specifically at the Brownlow Hill site of William Reid’s factory and the Shaw’s Brow site of Samuel Gilbody’s factory.

Among the many archival sources he reviewed were corporation lease registers, rate books, fire insurance records, newspaper advertisements, polling lists, and freemen’s books. Hillis verified the location of William Reid’s factory on Brownlow Hill, for instance, by scrutinizing the lease register and a 1765 survey map, both preserved in the Liverpool Record Office (pp. 13–15). A Sun Fire Insurance policy dated October 22, 1746, provides the first mention of Richard Chaffers and Philip Christian as potters, plus documents their partnership in a pothouse on Shaw’s Brow (p. 139). On the other hand, the fact that Hillis was unable to find any documentary evidence for William Ball’s Ranelagh Street Pothouse, to which objects formerly were attributed, led him to conclude that the factory did not exist (pp. 494–95).

Hillis’s equally fruitful examination of sherds and wasters was especially critical in helping him to identify wares from the William Reid and Samuel Gilbody factories.[5] Many photo captions in the chapters for those factories mention the existence of sherds matching a particular feature of the illustrated object. Regarding the output of Thomas Wolfe & Company, Hillis credits Alan Smith, whose 1968 recovery of sherds from the factory’s site in Islington not only enabled later writers to attribute wares to this short-lived concern but also demonstrated that the factory produced a hybrid hard-paste porcelain and specialized in transfer-printed tea wares (pp. 477–78).

Hillis has visited many British and North American collections in order to inspect thousands of examples of Liverpool porcelain, as well as comparative examples from other factories. Every reader can benefit from the author’s unparalleled knowledge based on this decades-long effort. What English ceramics enthusiast would not enjoy learning that one can tell the difference between a Worcester teapot and a teapot of similar form by Philip Christian’s Liverpool factory because the underside of the latter’s lid flange is glazed whereas the former’s usually is not (p. 244)? Or that the high Chelsea ewers made by John Pennington can be distinguished from those made by Philip Christian, and later by Seth Pennington, because John’s ewer usually has an oval foot rim rather than an eight-lobed one, as well as a handle that is thicker and set lower on the vessel (p. 357)? Such satisfying morsels of connoisseurship are available on virtually every page on which Hillis discusses the products of the Liverpool factories.

Moreover, when lack of archeological evidence requires Hillis to rely solely on extant objects, his extension of a few definitive traits of a given factory’s wares into a fuller repertoire of characteristics identifying that maker is like watching a seasoned detective. Such was the case when Hillis endeavored to attribute wares to the factory of John Pennington, and later to his widow, Jane, who continued the factory after her husband’s death. John and Jane Pennington’s factory produced bone-ash porcelain. Hillis recognized that a number of bone-ash porcelain jugs had identical mask spouts and that some of the jugs bore dates ranging from 1772 to 1774. This period coincided with Philip Christian’s years of production, but Hillis was able to eliminate Christian as the maker of these jugs because his factory made only soaprock porcelain. John Pennington’s brother, James, was making bone-ash porcelain until 1773, but Hillis was able to eliminate him from consideration because one of the documentary jugs was dated 1790, long after James stopped making porcelain yet coinciding with the period when Jane Pennington was running the factory. Once Hillis was confident that the mask-spouted jugs were made at John and Jane Pennington’s factory, he could then study them for other distinctive features, such as the type of handle employed, and look for those on other ceramic forms (pp. 319–24).

While Hillis’s primary objective is to identify the full range of wares made at each factory, he loses no opportunity to showcase exceptional works, for another important goal of his is to challenge the ingrained perception among many collectors that Liverpool porcelain is of inferior quality to that made by other English factories. Hillis acknowledges that Liverpool factories, like many others, catered to a variety of markets, including those at the lower end of the economic scale. Nevertheless, he demonstrates that many Liverpool examples would hold their own against the best of its competitors. There is, for example, the covered vase, more than thirty inches tall and painted with a continuous Chinese landscape in underglaze blue, that was made at the Richard Chaffers factory (p. 215). Or the large Samuel Gilbody jug delicately painted in polychrome enamels and featuring a Chinese junk sailing from its jetty on one side and a tall British ship on the other (p. 303). Hillis also includes a number of very rare forms, such as a cream basket and spoon made by William Reid (p. 70), a holy-water stoup by Philip Christian (p. 267), and a James Pennington sauceboat in the shape of a duck (p. 124).

Hillis’s comprehensive knowledge of Liverpool objects comes to bear significantly not only in the nine chapters focusing on individual factories but in three others as well. The first of these presents an illustrated list of all dated Liverpool porcelain known to the author, of which there are more than sixty examples. They are arranged in chronological order and briefly described, and for the reader’s convenience Hillis indicates which ones are in public collections. The other two chapters address underglaze-blue and overglaze-enamel transfer-printed decoration on Liverpool porcelain.

In the chapter on underglaze decoration, Hillis describes some 120 patterns, the most comprehensive list ever published. He names and illustrates each pattern and, most important, indicates which Liverpool factory or factories used the pattern. He also indicates when different versions of the same print enable one to make an attribution to a specific factory. For instance, two versions of the Chinese Lady with a Bird in a Cartouche pattern were developed, but one was used only by John Pennington, while the other was used only by his brother Seth (pp. 428–29). This chapter alone will make Hillis’s book an essential addition to the libraries of Liverpool porcelain collectors and other enthusiasts. The one regret is that the illustrations in this chapter are generally smaller than those in the individual factory chapters, so if the pattern under discussion happens to be fairly complex, its component parts may not be clear.

The author does not use the convenient list format for the enamel-printed patterns, but he reviews a wide variety of designs and always identifies the factory using the pattern. He focuses special attention on John Sadler, the renowned Liverpool printer who almost certainly bought Worcester and Longton Hall porcelain blanks to decorate and then resell but whose relationship with the Liverpool porcelain factories is more complicated. Sadler probably bought Liverpool blanks as well, but Hillis offers evidence indicating that Chaffers, Gilbody, and Reid commissioned Sadler to decorate their wares, which the respective factories would have then sold on their own. The Christian factory, meanwhile, might have been capable of doing its own enamel printing (p. 533; also p. 231). Hillis identifies Liverpool ceramic printers other than Sadler who possibly decorated porcelain produced in the city. He calls for more research to understand these Liverpool printer-factory relationships.

The last chapter addresses the marketing and distribution of Liverpool porcelain. Hillis specifies the newspapers, both local and as far away as in America, in which some of the Liverpool factories placed advertisements. He also lists place names inscribed on Liverpool porcelains or at which Liverpool sherds have been found, suggesting the geographic range of the factories’ markets. Ceramics in America readers will be interested to know that these archeological sites include Colonial Williamsburg; Portsmouth, New Hampshire; and Fort Michilimackinac, Michigan.

Minor inconveniences arise in using Liverpool Porcelain as a reference. For instance, the index could be more complete. Josiah Wedgwood, Robert Hancock, and other individuals important to the history of English ceramics (if not necessarily to Liverpool porcelain) make guest appearances in the chapters but are not listed in the index. In addition, with the exception of the public-collection photographs in the chapter on dated Liverpool wares, names of the objects’ owners appear only in a photograph-acknowledgments section. For readers wishing to see these pieces in person, credit lines in the captions would have been helpful, especially for objects owned by public institutions. Finally, it is not clear why the two chapters on printed decoration are not consecutive: underglaze patterns are the subject of chapter 9, enamel patterns are addressed in chapter 14.

These are trifling concerns that do not detract from the author’s herculean accomplishment, made all the more impressive by virtue of the fact that Hillis published the work himself. He has produced a meticulously researched, profusely illustrated text that will help scholars, collectors, dealers, and others to understand, at last, the historically complex subject of Liverpool porcelain. His publication manifests the scholarship and careful analysis that lie behind it, ensuring that it will be the definitive source on Liverpool porcelain for many decades to come.

Brian Gallagher

Curator of Decorative Arts, The Mint Museum

brian.gallagher@mintmuseum.org

[1]

Previous publications by Hillis on topics related to Liverpool porcelain include Maurice Hillis, “The Analysis of Shards from the Brownlow Hill Site in Liverpool,” English Ceramic Circle Transactions 18, pt. 2 (2003): 335–38; Maurice Hillis, “The Liverpool China Manufactory of Wm. Reid and Company: A Survey of Wares,” English Ceramic Circle Transactions 18, pt. 1 (2002): 58–90; Maurice Hillis, “The Porcelain of John and Jane Pennington, c. 1771–1794,” Northern Ceramic Society Journal 6 (1987): 1–22; Lyn Hillis and Maurice Hillis, “Late Christian or Early Pennington?,” Northern Ceramic Society Journal 5 (1984): 29–32. Hillis also served as chairman of the Northern Ceramic Society from 2001 to 2012.

[2]

The first author to write an account of Liverpool porcelain was Knowles Boney, Liverpool Porcelain of the Eighteenth Century and Its Makers (London: B. T. Batsford, 1957). He included wares now known to have been made in London, Staffordshire, and Worcester. Bernard Watney, in his two-part article “Four Groups of Porcelain: Possibly Liverpool,” English Ceramic Circle Transactions 4, pt. 5 (1959): 13–25, and English Ceramic Circle Transactions 5, pt. 1(1960): 42–52, made a groundbreaking effort to attribute works to specific factories, but he too included wares made in London and Staffordshire. He corrected this error in his Liverpool Porcelain of the Eighteenth Century (Somerset, Eng.: Richard Dennis, 1997).

[3]

With the exception of Thomas Wolfe’s Islington China Works, which produced a hybrid hard-paste porcelain, eighteenth-century Liverpool factories exclusively made either soft-paste porcelain with bone ash or soft-paste porcelain with soaprock.

[4]

Forms include coffee pots, cups and mugs, teapots, jugs, sauceboats, plates, and dishes.

[5]

The Liverpool Porcelain Rescue Group (LPRG) conducted digs at Reid’s factory site on Brownlow Hill in the late 1990s. Alan Smith excavated Gilbody’s factory site at Shaw’s Brow in 1966. LPRG conducted a second dig there in 1990.

Author

Hillis, M

Date

2011

Binding

Cloth binding

Publisher

Hillis

Condition

Book near fine, wrapper very good having a small dent to front

Pages

x, 564

Friends of the PBFA

For £10 get free entry to our fairs, updates from the PBFA and more.

Please email info@pbfa.org for more information